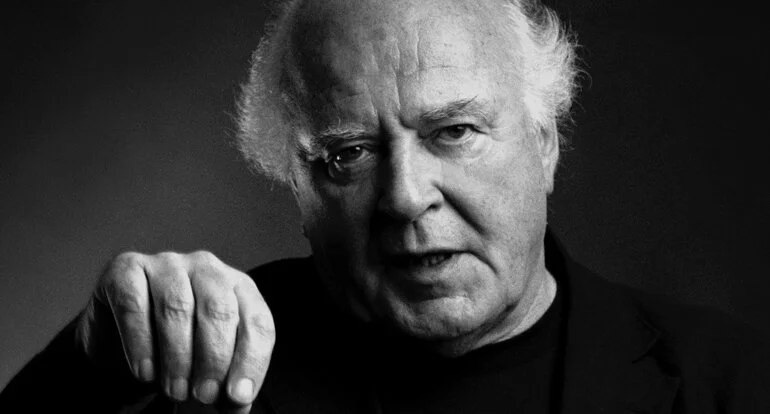

Christian Berger (AAC, BVK, AIP Honorary Member) is an Austrian cinematographer, director, producer, and writer of numerous documentaries, made-for-tv films, and features. As a cinematographer he worked, among many, for directors as Michael Haneke, Amos Gitai, János Szász, Angelina Jolie, Terrence Malick. In 2010 Berger was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Cinematography for his work on The White Ribbon directed by Michael Haneke and won the ASC Award for Best Cinematography for the same movie. Berger developed the new “Cine Reflect Lighting System” (CRLS) in collaboration with Christian Bartenbach: in addition to creating new esthetic possibilities for the camera, this system gives actors and directors unprecedented flexibility and freedom. He is married to actress Marika Green, and is also the uncle of Eva Green.

What sparked your interest in cinematography?

So actually I do not know exactly. Already as an 8-year old, I got at Christmas my 1st camera ‒ a kind of Agfa click-clack machine ‒ I have inserted a film with it still on Christmas Eve and made with it completely underexposed shots (with probably 25 ASA at that time). Then I wanted to secretly look, in the bathroom, where the photos were. I took out the film and looked intensively where the photos had gone. Since I could not discover anything, I saw only a film strip with a brownish emulsion layer and perforation holes at the edge ‒ so my interest and my very pronounced curiosity was aroused... But I had to learn this the hard way – it was the first lesson.

Christian Berger with a 16 mm Arri St model camera

Which film of the past has impressed you most in terms of cinematography in your artistic training?

I don't think it was a single film, it was rather the entire art form of film that gave my young lifestyle momentum – I felt the same way as with music, but visually. The abstract of the black and white, the aesthetics of light and shadows, of forms and the fleetingness of time and speed gave me the "fodder" for my desire to observe. Especially the Nouvelle Vague from France has fascinated me and finally radically renewed the "old cinema" of the 50s and 60s ‒ but finding my place in the film world seemed almost impossible to come – there was simply no market to speak of. Not only the cities were in ruins, but also every cultural landscape lay on the ground especially in the German-speaking area...

How did you become a cinematographer?

For me meant a camera is cinema and vice-versa cinema meant a camera. It wasn't literature, it wasn't theatre - it was images... Of course, I was not yet a cinematographer, but I was simply convinced that I would do it ‒ but I had no idea how and when. I lived in Tyrol and there was almost nothing with film after the war (not even in Austria or Germany at that time, with very few exceptions, which you also did not get to see). After my angry departure from the schools in Tyrol (as a young student that I was) one had the free choice at that time between teachers who were either militant Catholics or former NAZIs. I went into an apprenticeship as a lighting technician. That was a light-technical planning office in Innsbruck around with and for architects - new buildings, supermarkets, hospitals office buildings or also street lighting or sports stadiums etc. to illuminate. But I only wanted to go to the film. At that time, of course, the connections and the importance of the light for the camera were not yet clear to me. Then I found a job as a camera assistant in a film studio in Linz. After a year I think I could only turn on a camera twice, otherwise, I did a lot of cleaning, cables, tripods, spotlights and of course cameras. Once I used the camera on a trick table, that meant I "filmed" frame by frame, 24 frames per second an animation film with a Polish director.

A very young Christian Berger with a 16 mm Bolex Paillard model camera

Christian Berger with a Moviecam camera

In the end, he didn't have the money to pay me and offered me his camera as payment, a Pentaflex 16 with 3 super original Zeiss lenses. But that was worth more than my work ‒ I had to pay something extra with my father's money… In the evenings I was a projectionist in an arthouse cinema. I wasn't a very good projectionist because I preferred to watch the films through the small projection windows until I noticed when the carbon arc lamp in the projector burned out or I overlooked to switch to the next film reel... That year was a Tuition fee also a kind of film study. So I was almost a cameraman. Back in Tyrol in 1968, there was a new position in the regional studio for the ORF as a news cameraman for local broadcasts. The director had asked me “Can you film and also do journalistic work?”. Of course, I said yes and jumped into the deep end. After three years I was able to start my first small film production and after ten years I came, together with two teams, to more than 3000 reports, magazines, documentaries and with every money that remained, I could realize my own independent short films. I don't regret this "apprenticeship", even if this way of filming didn't live up to my dreams. But I had my Pentaflex, Arriflex BL16, CinemaProduct 16 and finally my first Aaton S16 in my hands almost every day and, if you do not become cynical or alcoholic, you can learn and see a lot. Then it continued with work for the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation (ORF) and

Christian Berger with a 16mm Aaton model camera

German TV stations with TV dramas, documentaries and in 1983 I was able to realize my first own feature film Raffl with very dedicated and good collaborators. I had never expected how much this film would be noticed internationally. So I realized for the first time how important it is in our profession to look as closely as possible, to observe. With great precision in the small things, the big things open up. For this you need accuracy, perseverance and patience, I really believe that without these qualities there is no art. Even if great precision always involves the risk of becoming hard and narrow. And I'm really grateful that the experience of working much with documentaries has been an excellent school for me - I couldn't imagine my work later in feature films or in-studio work and working with actors, or even in lighting without these practices. I was then able to realize 2 more of my own feature films Hanna Monster, Darling (1988) and Tollgate (1993). Doing my own projects also as a director (and producer) was never really my goal - those years of struggling to write and finance tired me a lot and the image (the camera) was more important to me anyway. After that, I decided to dedicate myself more to the image and the light.

What can you tell me about your collaboration with director Michael Haneke? With him, you have collaborated on several films such as Benny's Video (1992), 71 Fragmente einer Chronologie des Zufalls (1994), La pianiste (2001), Caché (2005), The White Ribbon (2009), Happy End (2017).

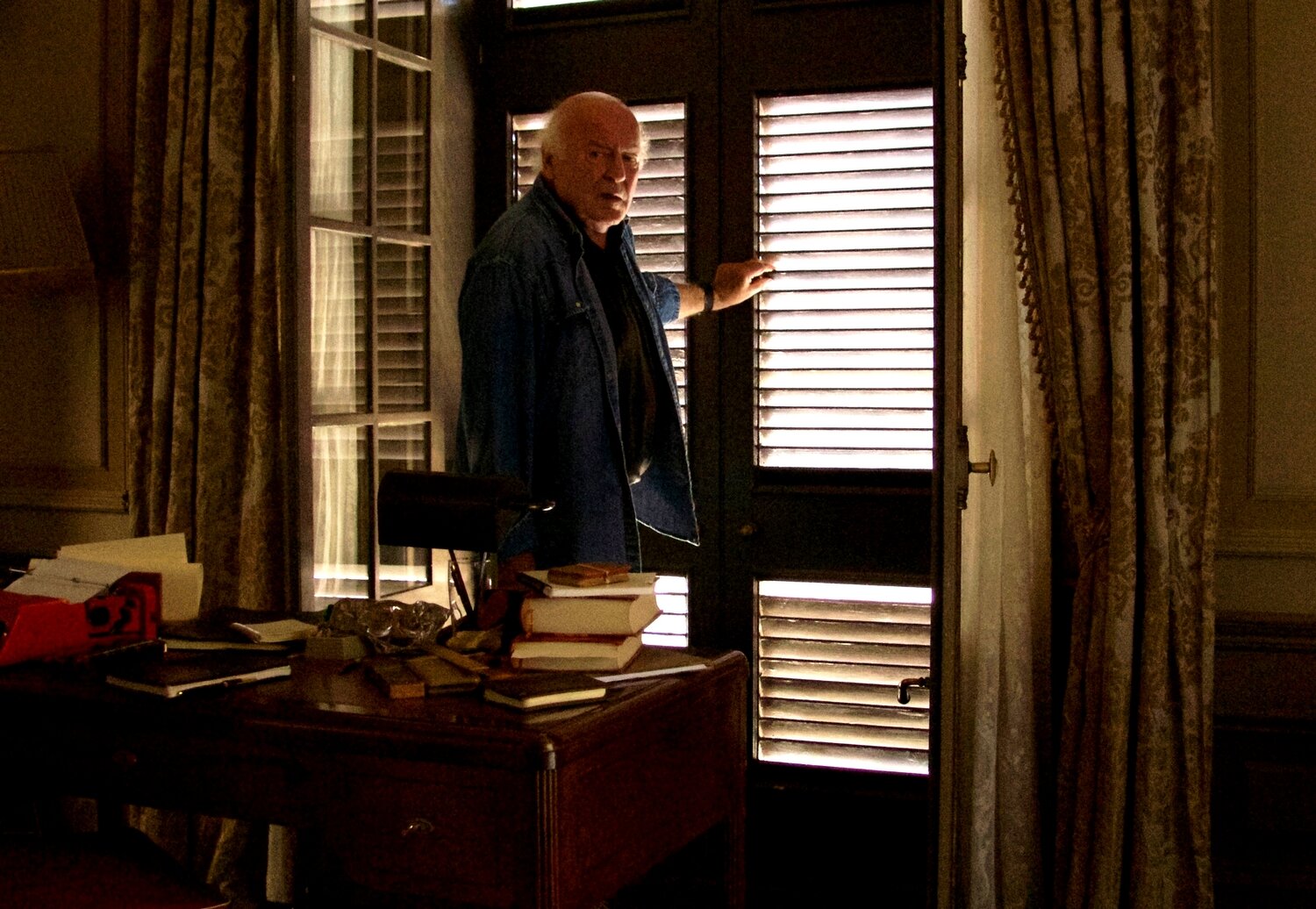

Christian Berger with director Haneke on the set of Happy End (2017)

Michael Haneke liked my film Raffl, which is probably why he wanted to make his first feature film with me (The Seventh Continent), but I was busy with Hanna Monster, Darling and that's how the first collaboration came about with Benny's Video. In total, we worked together on six of his films. I'm actually only sorry that the collaboration for Code Unconnu didn't work out because I really appreciate that film. And Jürgen Jürges did very good work. But basically, I like Michael's obsessive accuracy. Knowing myself, it was not always easy to work with him (or him with me). But I respect and appreciate the result of this work very much.

Christian Berger with director Haneke on the set of The Pianist (2001)

The White Ribbon, in particular, photographed in magnificent black and white, represents the highest of your collaboration. With this film, you are nominated for an Academy Award for Best Cinematography and you have been awarded by the American Society of Cinematographers (ASC) as best cinematography. Among other things, the film won the Golden Palm at the 62nd Cannes Film Festival. What can you tell me about the stylistic and photographic choices?

The White Ribbon directed by Michael Haneke (2009)

I hope I'm not interpreting anything here that Michael sees differently in retrospect. Of course, we looked at photos from that time (at the beginning of World War 1) and, of course, there were pictures from that time only in black and white. But that's not the main thing. For the camera was important to me not to get nostalgic about the black and white, so to speak. After all, the story of this film was so effective for the present through Haneke's stylistic stringently and handwriting, and it was understood that way. I tried to modernize through the design of the light and the texture of the B/W, to make it present-day, if there is such a thing at all... About the framing ‒ also in this film ‒ we have very rarely conversations or discussions necessary; first of all, because Michael has very clear ideas, and secondly because I have very similar clear ideas or preferences, image details or movements – about the whole shooting list. Apart from that, I like very much how clear and concentrated Michael makes the shooting list in advance on the most necessary, and it gives me the best clues for designing the atmospheres of a scene. This makes the planning of the shoot for the whole team and the dimensions of the effort for the organization of the production very efficient. Moreover, I don't know a better way to ensure the result in relation to the script and Michael's intention.

Is it correct that all the scenes were originally shot in colour and then changed to black and white?

The White Ribbon directed by Michael Haneke (2009)

For us, it was clear from the beginning to shoot in B/W without any doubt ‒ there were only production-related financing requirements from a participating television station that was against producing in B/W or would have dropped out. So we were obliged to deliver at least a broadcast-ready colour version. This caused me some difficulties during the shoot (especially with the mixed light colour temperatures of day and night) but also the illuminants, HMI, tungsten, kerosene lamps, torches and fire. After many tests and with the best Kodak negative materials (in 2008), we saw that logically the large and rich colour space of the negative in the transfer to B/W allowed a much richer grayscale than the original B/W could show at that time. We thought and checked only in B/W... In retrospect, the TV station never asked for a colour version - how brave! Apart from that, The Withe Ribbon was the last analog work for me and the last work where I operated the camera myself. And that still makes me a little proud. Even though none of us could have foreseen this great success. Actually, in every important work, even during the shooting of one scene or another, you know, ah, this is a masterpiece! That's recognizable ‒ but you never know beforehand whether it's the whole film and how will it be received...

The Cine Reflect Lighting System for Happy End (Michael Haneke, 2017)

Before filming began, you studied the black and white films that Ingmar Bergman made with great cinematographer Sven Nykvist ASC-FSF?

I didn't have to study anything - his B/W work was immediately present to me (even while reading the script). He was almost an idol for me in my younger years ‒ he found and made quite wonderful pictures and the mastery of his "craft" always impressed me deeply. I think that this understanding of light and the power of the actors' sensitivities and his power to create atmospheres were certainly formative impressions for me. The reduction, the omission of everything superfluous - simplicity is mastery!

What can you tell us about Disengagement (2007) a film directed by Amos Gitai, starring Juliette Binoche, with Jeanne Moreau in a supporting role?

Christian Berger on the set of Disengagement, with director Amos Gitai and actress Juliette Binoche (2007)

What a contrast with Amos Gitai after my experience with Michael Haneke! 180 degrees! What is pre-planned and foreseeable with Michael is completely opposite with Amos! His accuracy and precision consists in avoiding planning, avoiding rehearsals, and thus surprising the actors and all of us ‒ the whole team and perhaps himself too. I have come to appreciate his very, very sure "instinct" to use this method to explore and test the full potential of a scene, of the actors. For Juliette Binoche this was only possible because she knew him and got involved from the very beginning - while the camera is running - Amos tells her with his megaphone in the text breaks, ... don't go to the window, go to the door, leave out the coming sentence... and so on. And for me, it was like that too - on the one hand working under normal feature film conditions and suddenly I had to behave, on my own, like in a documentary, I could never know what was going to happen in the next moment because suddenly the positions changed almost 360° except the few unavoidable degrees for the camera and Amos with the megaphone behind my back. Juliette was doing something that I was supposed to "anticipate" ‒ this often "forced" me to convert unexpected actions into flowing camera movements ‒ but not with a shoulder camera but directly with the dolly and so the light in the rooms had to cover almost all directions - this was really exciting and often really "beautiful". It was like dancing and served the story and helped the actors. Interesting and nice to work like that

Chstian Berger and Juliette Binoche on the set of Disengagement (Amos Gitai, 2007)

and at other times fun for all involved. For example, the whole ending of the film unfolded in this way as it was written in the book - during the shooting of the prepared final scene in which Juliette runs out of the frame and that was meant to be the final title background... the camera is running and Amos suddenly calls through his megaphone to Juliette... come back in the frame, come back... and Juliette has come back. Suddenly there was an incredibly emotional ending to the whole film and her partner was also involved again, who was actually already finished - and I was happy to have started this take fresh with a full cassette and shivered until the last meter ran out, and it was really the last meter...

I have another little anecdote ‒ the first time I met Jeanne Moreau on the set I really almost blushed ‒ I told her...you know as a young man when I saw you for the first time in Moderato Cantabile a film by Peter Brook - it was clear to me: I have to find a way into the world of film. I guess I was a bit in love with you... and she answered me after a little pause...and today not anymore? So, was a very nice shoot with Amos Gitai and I was proud that my light system CRLS (although still a prototype) made this kind of shooting possible.

By the Sea (2015) is an American romantic drama film written and directed by Angelina Jolie Pitt, and produced by and starring Jolie Pitt and Brad Pitt. What were Angelina Jolie’s main demands from a cinematographic point of view?

Christian Berger on the set of By the Sea, written and directed by Angelina Jolie (2015)

One of them was to capture correctly the spirit of the 70’s in the south of France. Reproducing the feel of that time was essential, which is how we came to reference the Nouvelle Vague, a movement that was very important for me during my younger years. It’s a mix of humour and “tristesse.” For me, there is no need to have rainy autumn days for a sad scene – and it can be very funny in a dark corner.

Which filmmakers influenced you from that era, Nouvelle Vague and beyond?

I especially liked Jean-Luc Godard and most of the French directors, and also the Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman, without forgetting Roberto Rossellini from the Italian Neo-Realism movement, amongst others.

Why do you believe Angelina Jolie Pitt and Brad Pitt chose you for this movie?

I believe they chose me because of my Cine Reflect Lighting System. And that was a very nice thing for me to hear because it is a new way of thinking about lighting. Because this is so important to me, it changes how you can light a set – so much more than to use just a new technical device.

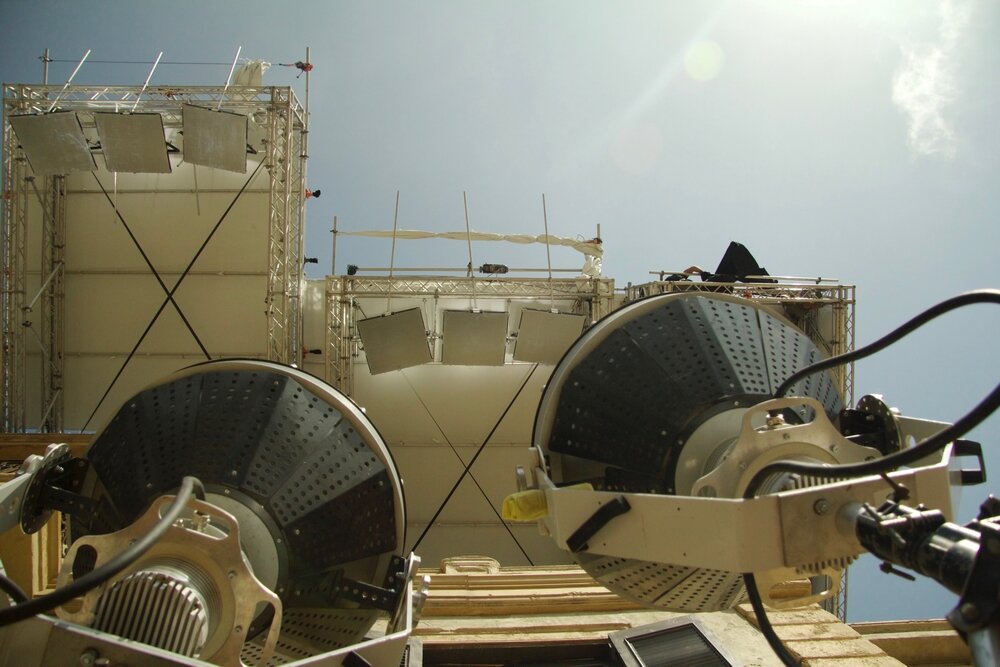

The Cine Reflect Lighting System for By the Sea (2015)

When did you come up with this revolutionary lighting system, known for short as CRLS?

I started using it in the year 2001 with Michael Haneke’s The Piano Teacher, and from then on I have used it on all my movies, developing it step by step.

What are its qualities?

First, it allows you to come close to the beauty of natural light and then it enables you to create a safe space for actors and also for directors by reducing the technical clutter on a set, which was very useful in By the Sea. My gaffer Jakob Ballinger just created a website for directors of photography and gaffers to educate and involve them with the further development of the CRLS – www.thelightbridge.com.

It is based on the observation of natural light, right?

Yes, I observe natural light as precisely and patiently as I can, because it still has its secrets and it is still the best teacher to learn from. Observation reveals the richest and most beautiful atmospheres we can know. Nature never uses several lamps. There is basically only one main source (the sun). Light itself is invisible. We only see reflected light, which is shaped and formed by the surfaces which are, so to say, “obstacles in the way” of light. So any kind of surface -- a landscape, a wooden floor, or a human face – defines the appearance of light for our eyes. I only have to give the light a chance to do what it does best: evoke the emotional values that serve human perception.

The Cine Reflect Lighting System for By the Sea (2015)

How did you achieve this on By the Sea?

I use a lamp with parallel light beams (as near as possible to the quality of daylight) and a set of high-tech reflectors to modulate and direct the light how and where I want to have it. With conventional lighting, you normally sense the different sources – with that feeling that there is a lamp shining on something. I prefer the person to shine with his or her own light, like in the best paintings. And I think painters did precisely that: they observed how natural light behaves and used it to realize their artistic visions. Besides the special – I call it “transparent light quality” – the CRLS changes the working method. We had an uncluttered, free set. For example, in the hotel room where a large part of the story takes place, there were no cables, stands, flags or filters.

How does that simplify the work of the actors on set?

For one, it means that we wait for the actors to be ready, rather than them waiting for the crew, which is what happens on so many other sets… Secondly (and this made Angelina and Brad very happy), they can move where they want, they gain that “imaginary space” actors refer to. It is so important for them! It’s not inspiring for actors to be surrounded by electrical equipment and technicians while they are trying to say, “I love you”. “When we did scenes,” says Jolie Pitt, “we didn’t have big lighting setups in our face for close-ups.” “We … experiment and play,” adds Pitt “and it’s oddly a safer environment than any set I’ve been on before. So we let loose!” (Quotes from «Vogue» magazine behind the scenes teaser).

The Cine Reflect Lighting System for By the Sea (2015)

By the Sea has been shot on the island of Gozo, in Malta. How were the filming conditions?

Yes, and in an empty bay production designer Jon Hutman had to build a hotel and a café. We had an interesting mix of studio and on-location conditions, which resulted in many challenging light situations. For me, it was like a studio “on the rocks.” It was not only hot in Malta, most of the time we had quite harsh sunlight. My gaffer Jakob Ballinger created a unique rig for the CRLS that allowed us to quickly change the required atmospheres from day to night and from night to day. Even on a rainy day, we could keep the “sun” stable or make a shady day if necessary. And we could always maintain a free view of the sea or the rocky hills through the windows of the set. But, despite the isolation of the location, it was a very professional production setting. I really have to compliment not only my crew but also the production crew I had on BY THE SEA because they were so good and efficient.

And what about the exterior shots?

I loved the horizontal structure in the nature that surrounded us, like the sea horizon or the coast structure, which was one of the reasons for shooting in Cinemascope. The most challenging situations were when we had to make night shots over the whole bay including the hotel and café.

By the Sea, written and directed by Angiolina Jolie (2015)

What would you say are Angelina Jolie Pitt’s main qualities as a director?

Angelina is very warm, straight and concentrated. I respect and like her speedy intelligence, hungry curiosity and 100% devotion to each scene – her unbelievable energy. She is always open and collaborative while looking for the best solution to any given problem. I was also impressed by her unique way of telling a story.

And as an actress (in the film she plays the role of Vanessa)?

Angelina has been professional and brave in exposing herself as an actress too. She took the risk and just focused on making each scene the best possible. I tried my best to make her life easier with her multiple functions – author, director and actress.

How was on set Brad Pitt, who played is her husband Roland?

Brad respected Angie as a director and focused on acting. His attitude was, “I’m your actor, so tell me what to do!” He has a great work ethic is just so much fun to be with. He surprised me with his comic talents.

Also with Jolie Pitt, you collaborated on a commercial directed by Terrence Malick. What do you remember about your collaboration with a great director like Malick?

Advertising Guerlain directed by Terrence Malick. Testimonial Angelina Jolie, cinematography by Christian Berger

I must confess I was a bit flattered ‒ I liked that Angelina wanted me for this Guerlain campaign and with Malick I had no personal contact so far. We then had a phone meeting a few days before the shoot and found him very sympathetic. I told him that for the time being I had no experience with advertising and he answered me: “No problem, that's the same for me...”. There was, of course, some kind of script and storyboard but, when we started shooting, Malick "exploded": “My very good steady-cam operator, Alex Brambilla from Rome, a real camera-bear, is really groggy after a long day”, and on the 2nd day again with almost 20h of material! Such a shooting ratio was also new for me! And Malick is a fan of wide-angle lenses, and me not, but we got along well and he has very curiously observed my light and liked to play around with the little CRLS reflectors themselves. Very nice to see that a director plays around with light for himself!

But you are also a director. What do you like most about directing a movie?

For my own three feature films, I was never of the opinion that only I must and can do everything myself. Basically, every role is at the expense of the other. In my case it was rather because I did not find anyone for writing and directing who would have corresponded to my intentions or visions, that would have actually relieved me. And I was also a producer, where, of course, I had to put confidence in a production manager. Maybe I was always too picture dominant. But after these experiences, I found it better to make my focus more decidedly on the image and the light. Besides, I still had enough directorial work for documentaries. And there it is obvious and expedient to think and work in personal union. Besides, today I am better and closer to the understanding of the work and the struggles of a director. At other times the job of the camera is that of a midwife, why not?

The set of Raffl directed by Christian Berger (1984)

Marika Green in Hanna Monster, Darling (by Christian Berger 1988)

Marika Green in Hanna Monster, Darling (by Christian Berger 1988)

Going back to the new Cine Reflect Lighting System… shortly CRLS, which you developed in collaboration with Christian Bartenbach, a worldwide respected and famous lighting engineer. Can you tell our readers what exactly it is?

The beauty of natural light has always been something impressive and exciting to me. From the beginning of my career as a director of photography, it was always my goal to protect and achieve this particular quality in my work. Not a simple thing with conventional lighting. I always wanted the actor lights up, a face or a landscape, not a lamp. The beauty of natural light consists of objects and surfaces that reflect light – they define the atmospheres – not the source. Light itself is invisible, you can only see it if there stands something in his way. Place a luxmeter in outer space ‒ in the deepest darkness we know ‒ and it will show you around 100.000 Lux because your lightmeter is hit by the light. The reflected light is nothing new for the film industry, there are always a lot of reflective surfaces, be it a white wall, a green tree or a sandy ground, and since ever we are using reflectors to brighten up shadows and so on. But when I discovered the lighting technology of Christian Bartenbach, which he developed in his light laboratory to redirect light,

Christian Berger and Christian Bartenbach

for example, into large buildings or under the earth, I realized how the film industry could benefit from this knowledge. Inspired by that I started playing with specially built light solutions for the films I was working on. Slowly leaving the beaten path of standard lighting solutions I realized how many people in different professions also find great solutions to master challenging light tasks. Back to the good old rule of “observe the nature” I tried to recognize the path of a single light beam to find out the “behaviour” of the light in general. So I understood after a while that it is much better to flow with the light instead of forcing it with my stubborn intentions. Suddenly I reached very organic and rich images with high transparency which supports our perception to feel spatiality. No smearing, soft but with a punch. Directing the light very precise where I want to have it. Under complete control. This was the birth of the Cine Reflect Lighting System. At that time, I had no idea how many ups and downs and years it would take before we could serve the smallest set as well as a large studio. Together with my gaffer Jakob Ballinger we are proud to present a very precise lighting system “fit for the set”. The CRLS – Cine Reflect Lighting System. Now we have finally a system in our hands that is worth sharing with my colleagues.

Can you describe your process in the lighting of a scene?

The most difficult thing to light a scene well is to see a clear vision of the result and the appearance of the finished scene in front of your mind's eye... And the next step is then to find the simplest answer of the implementation and only then with which technical tools... Beyond that I find it most exciting to dare the border crossings, therefore I find darkness to "light up" much more difficult. To "make bright" is mostly simple… It has often happened to me that you get into a dead end and the solution usually works, everything just starts all over again. Back to zero and re-light. Correcting and improving something here and there usually only leads to a mishmash ‒ correcting usually makes things worse. I have learned that the most efficient way lies in the appropriateness of the effort in relation to the task at hand ‒ this can be both ‒ complex and complicated or very simple. And never say “I already know” or “I have already done many times”. Not good.

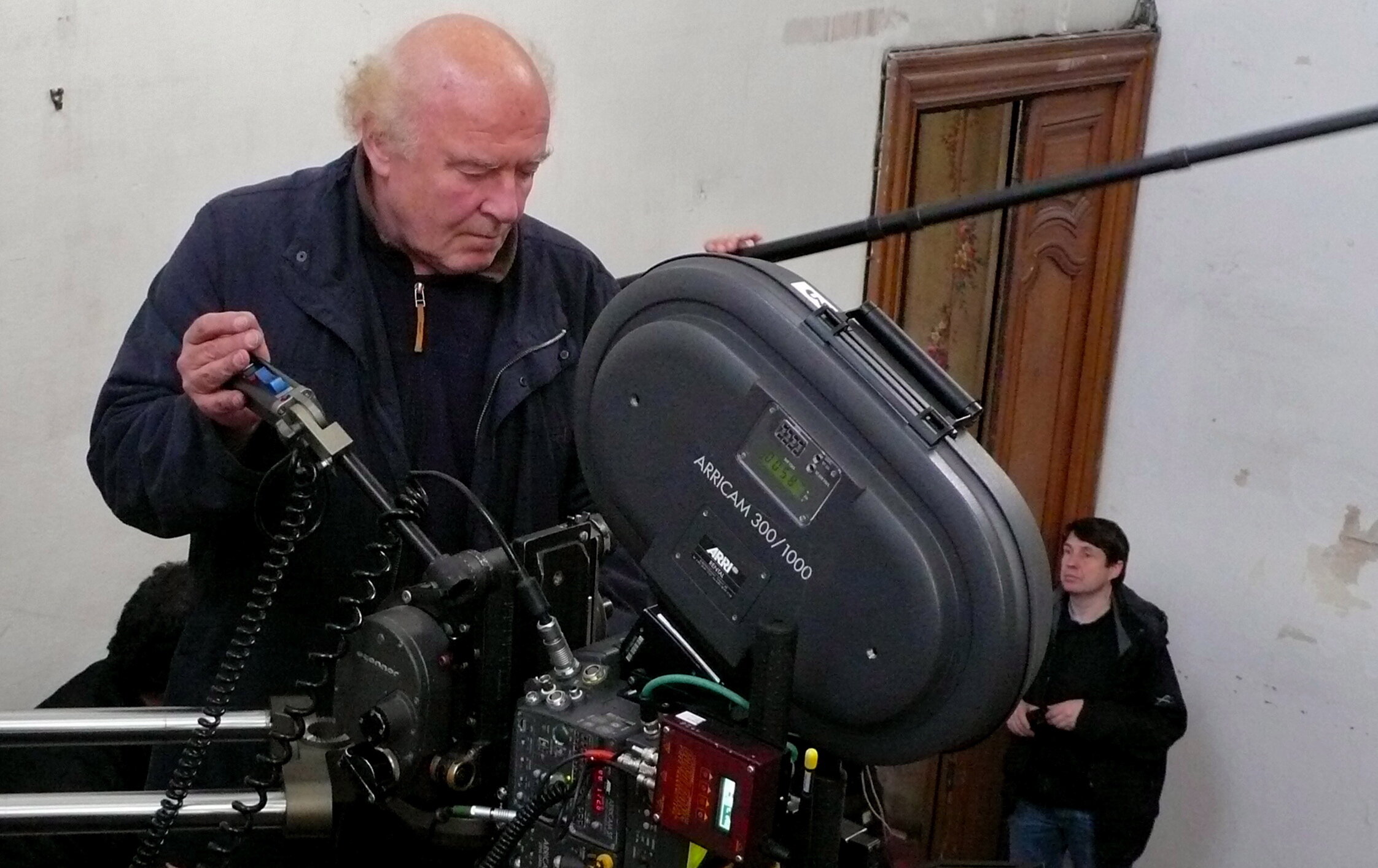

Christian Berger on the set of Disengagement with an Arricam model camera (2007)

New technology: what do you think of the epochal transition from film to digital?

Thank God this question is finally settled ‒ these endless almost religious discussions and quarrels analog/digital has given much cause but, at some point, it became borders that always arise when one technology replaces another ‒ and it arises fundamentalist rejection or pure redemption. I had very bad experiences with digital cameras for Cachè (2004) and shooting was hell. The promises of this technology gave us lied to the blue of the sky: "the future is now" (by the way something I have been heard for 30 years) and I really can't hear it anymore. And it was far out from any professional standards ‒ not only in the cameras but in the whole infrastructure for film production ‒ pure bullshit. The whole team but also the production said afterwards as long as there are no substantial developments, never again. I think after 2010 and with Alexa, there were good reasons to meet cinematic demands. Today I am pleased about the technical possibilities with a quality that I could only dream of in the analog time, which is also often idealized nostalgically. And now I can walk around with my little Fuji's and please myself with the ease and the playful possibilities to make new cinematic forms or documentaries ‒ and that can open new doors...

Over the course of your career, which camera model did you prefer?

I have already mentioned my 16mm time at the beginning (and Aaton "the cat at your shoulder" was by far my favourite camera for almost 20 years) and then in the years with 35mm I was a fan of the Moviecam (apart from the fact that Gabriel Bauer developed this camera in Vienna). The ease and possibility of spontaneity to shoot in the good old analog time is something I miss today sometimes (measured by professional standards) On the other hand, you have to say honestly, there were analog of course enough breakdowns, not so much with the equipment - but with the different Negativ materials there was never the "one" and continuously perfect quality ‒ ha, ha. Let's just think of the problems with the very different film materials and how long a reasonable development took in the dynamic range or up to 500 ASA (!)... And today the film students whine if they should not go over 3000ASA (ha, ha) or what do I know... As long as I still have a viewfinder and an ergonomic handiness ‒ OK. But I don't want to run around with a calculator, with 20 cables and div attachments that you can manage with it at all (don't laugh, it's not self-evident). And for professional work I was, just coming from Arri, also at Alexa in good hands, they have never forgotten what we need in our professions. I always looked for the most direct path from my eyes to the picture and that was the best camera, without obstructions – a clear eye line.

Christian Berger on the set of Ludwig II (Marie Noëlle and Peter Sehr, 2012)

Which Italian cinematographers, past and present, do you most admire?

I liked the work of Carlo di Palma (Deserto rosso) and Gianni di Venanzo (La notte). For today I feel close to the works of Luca Bigazzi and his light (La grande bellezza).

How do you think the pandemic will affect the film industry and especially its use by the public?

I really don't know ‒ these issues affect so much more than our "little problems" in our rather privileged industry. There are fears and hopes... But the film people do not like them so much. And the cinema people have to see that their projectors don't get rusty. And the audience will probably get used to the viewing habits on their cell phones.

Concluding…

I attach a little video to this interview to give your readers a bit of an idea of how it all came about with the CRLS, after 20 years of testing and developing the various prototypes... And I hope to give a new view on the methods of lighting and it is indeed something very simple and clear. This video is maybe a bit improvised but why not... It is for me a little freedom that the pandemic allows me. I also want to thank Gerry Guida, because he supported and inspired me with his interview. And I hope that I can inspire others too.

Official website: www.christianberger.at

Discover our books here

Discover our interviews with cinematographers and directors

subscribe to our newsletter

Active Light: Issues of Light in Contemporary Theatre

paperback and ebook

The Great Beauty: Told by Director of Photography Luca Bigazzi

paperback and ebook

On Suspiria and Beyond: A Conversation with Cinematographer Luciano Tovoli

paperback and ebook