In addressing the dramaturgy of light in theatre, two preliminary considerations may be advanced. First, contemporary approaches in this field tend to regard stage lighting primarily as something pertaining to the visual sphere, and only rarely—if at all—to that of time, action (that is, the action of light), or discourse. Yet these domains cannot be excluded from any thinking about dramaturgy, just as the visual dimension itself cannot be excluded.

Second, there remains a lack of conceptual clarity concerning what is meant by the dramaturgy of light, despite the fact that the foundations of such a concept were formulated with considerable precision as early as the late nineteenth century by Adolphe Appia [1], and that the history of theatre from that period onwards—and indeed prior to it—contains numerous significant instances of reflection on this matter [2].

What seems still to prevail is a relatively indeterminate notion of the dramaturgy of light understood as possible support, for example, to the dramatic text or to the dramaturgy of the actor.

Alongside my work as a theatre director, I led workshops on light for several years. Over time, these produced some twenty performances, presented to the public, made solely of light, objects, and sound; lacking, that is, those elements—text and actor—to which meaning and the dramaturgy of the work are usually principally entrusted [3].

The purpose of these workshops was to examine in depth the language of stage lighting, its capacity to articulate itself in a concatenated manner, and its potential to produce sense, discourse, and dramaturgy autonomously, just as music, for example, is capable of doing. In those works, light—understood also in its being time and action—was the principal element of dramatic texture.

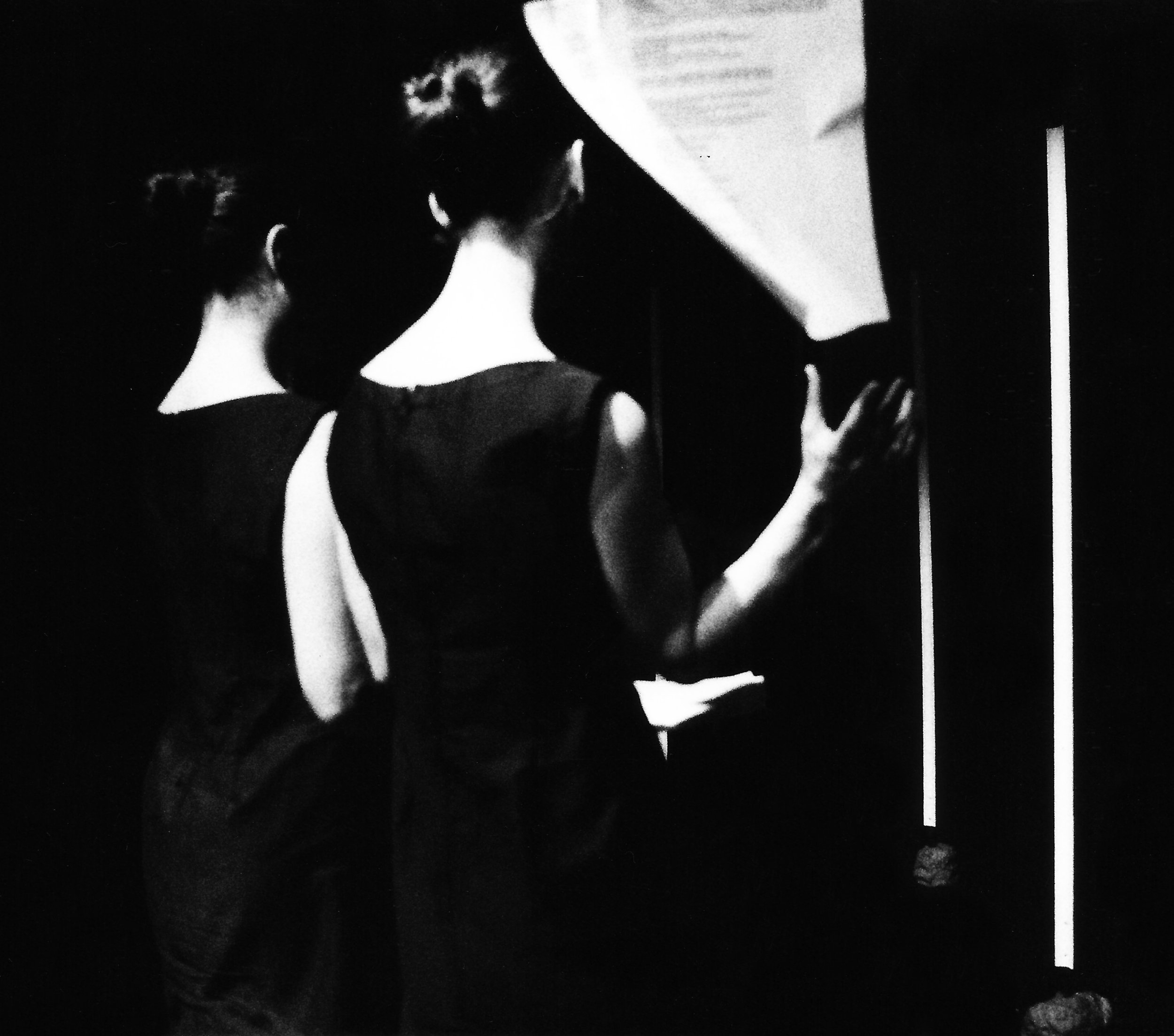

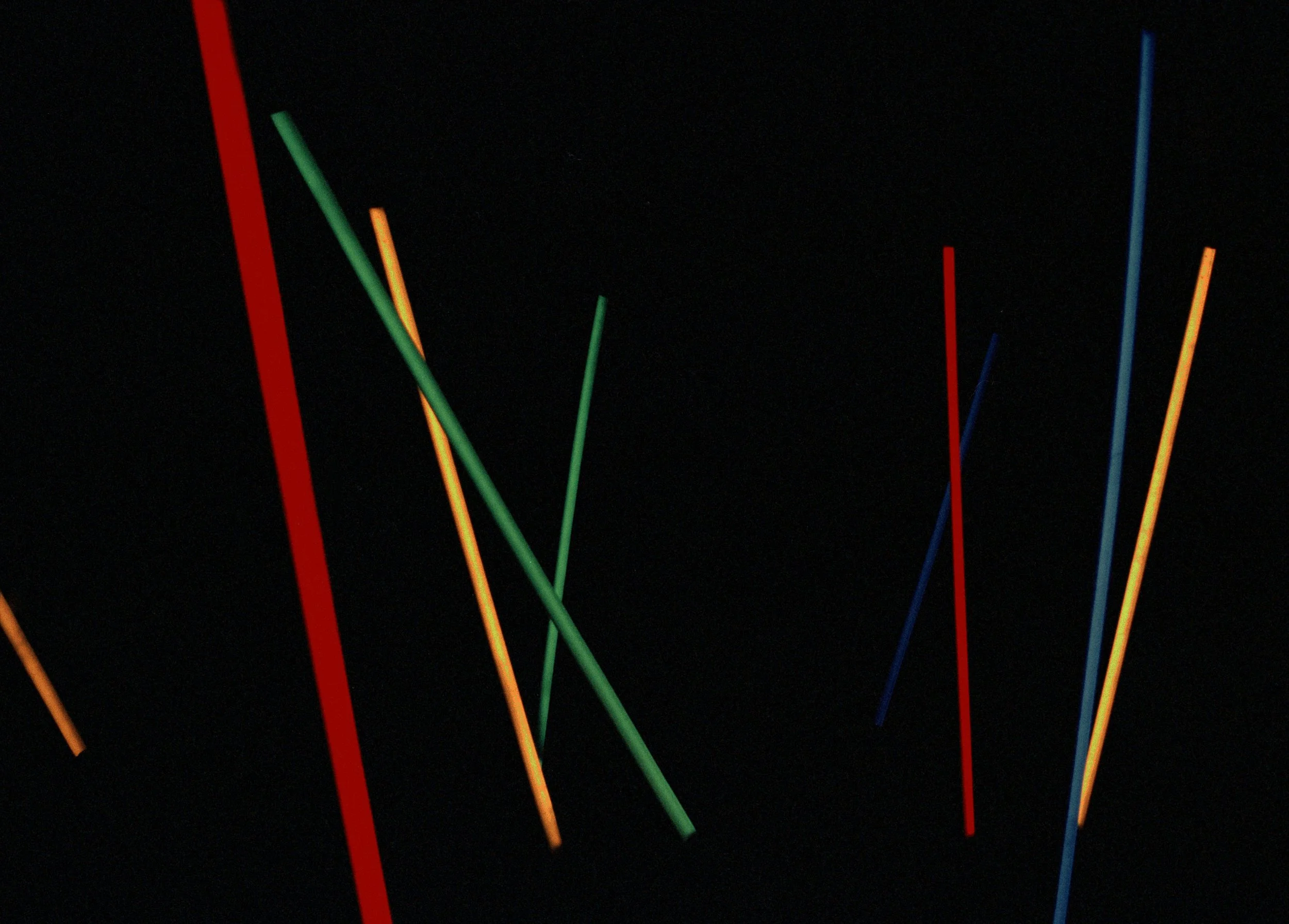

Folgore lenta (Slow Flash), by Fabrizio Crisafulli and Andreas Staudinger, direction, set design, and lighting design by Fabrizio Crisafulli, 1997 (photo: Udo Leitner)

That research convinced me further of light’s capacity to generate its own autonomous discourse. Applied to my directorial work within the productions of my theatre company from 1991 onward, it enabled me to establish for the performers a set of important and influential conditions external to them: conditions close to those of reality, in which light possesses its own independence and agency, exerting a substantial effect on us and on the ways we organise our lives and actions.

The intention has never been, nor is it now, to imitate reality. Rather, it has been to create on stage a poetic resonance of the real—both natural and technological—and to place the performers within a living context, fertile for their work.

A further prerogative of light that has been brought strongly into play by the workshops and by my company’s works—belonging primarily to the sphere of image—is form. This prerogative has assumed ever-greater importance in the evolution of stage lighting [4]. Technological innovation—particularly from the second half of the twentieth century onwards—has given a strong impetus in this direction (film and slide projections, profile spotlights, video projections, lasers and ‘solid light’ fixtures, digital and holographic images), identifying even more clearly than in the past the distinction between light ‘for seeing’ and light ‘to be seen’ [5].

Folgore lenta (Slow Flash), by Fabrizio Crisafulli and Andreas Staudinger, direction, set design, and lighting design by Fabrizio Crisafulli, 1997 (photo: Udo Leitner)

These are questions that, taken as a whole, academic studies on theatrical light are beginning to address. A book published in 2023 by Katherine Graham, Scott Palmer and Kelli Zezulka, comprising contributions from an international group of practitioners and scholars in the field of stage lighting [6], analyses—according to various interpretative approaches—the capacities of light to construct dramaturgies and create meaning. It declares itself to be doing so in response to the growing ‘critical understanding of the affective, dramaturgical and material contribution(s) of light to performance, and the value of light as an area of research’ [7]. The publications that, according to the editors, inaugurated this new phase are my book Active Light (2013 see note [2]; original Italian edition: 2007) and the volumes by Scott Palmer (2013) [8], Christopher Baugh (2013) [9], Yaron Abulafia (2016) [10], Nick Moran (2017) [11] and Torni Humalisto, Kimmo Karjunen and Raisa Kilpeläinen (2019) [12].

A special issue of the journal Theatre and Performance Design from 2013, entitled On Light [13], likewise places the dramaturgy of light at the centre of analysis, reiterating the expansion that has occurred in the field of light theories and practices over the last two decades and the sense of moving away from an idea of light as a secondary element, to recognise instead its vocation as a primary agent of performance [14]. This change of perspective has also been developed by the international conference Lumière Matière, held in two phases in France and Italy (University of Lille / University of Padua–Giorgio Cini Foundation, 2019–2020), curated by Cristina Grazioli and Véronique Perruchon, the proceedings of which have recently been published [15].

It seems to me that the idea of the ‘dramaturgy of light’ has by now been adopted as a foundational concept by scholars and designers in the field; yet, so that it does not remain merely nominal (and merely a matter of updating terminology, replacing, for instance, such inadequate yet widespread locutions as ‘lighting effects’ or ‘plays of light’), I believe it must be investigated in depth in its multiple aspects, at both the conceptual and the practical level.

A Light Score

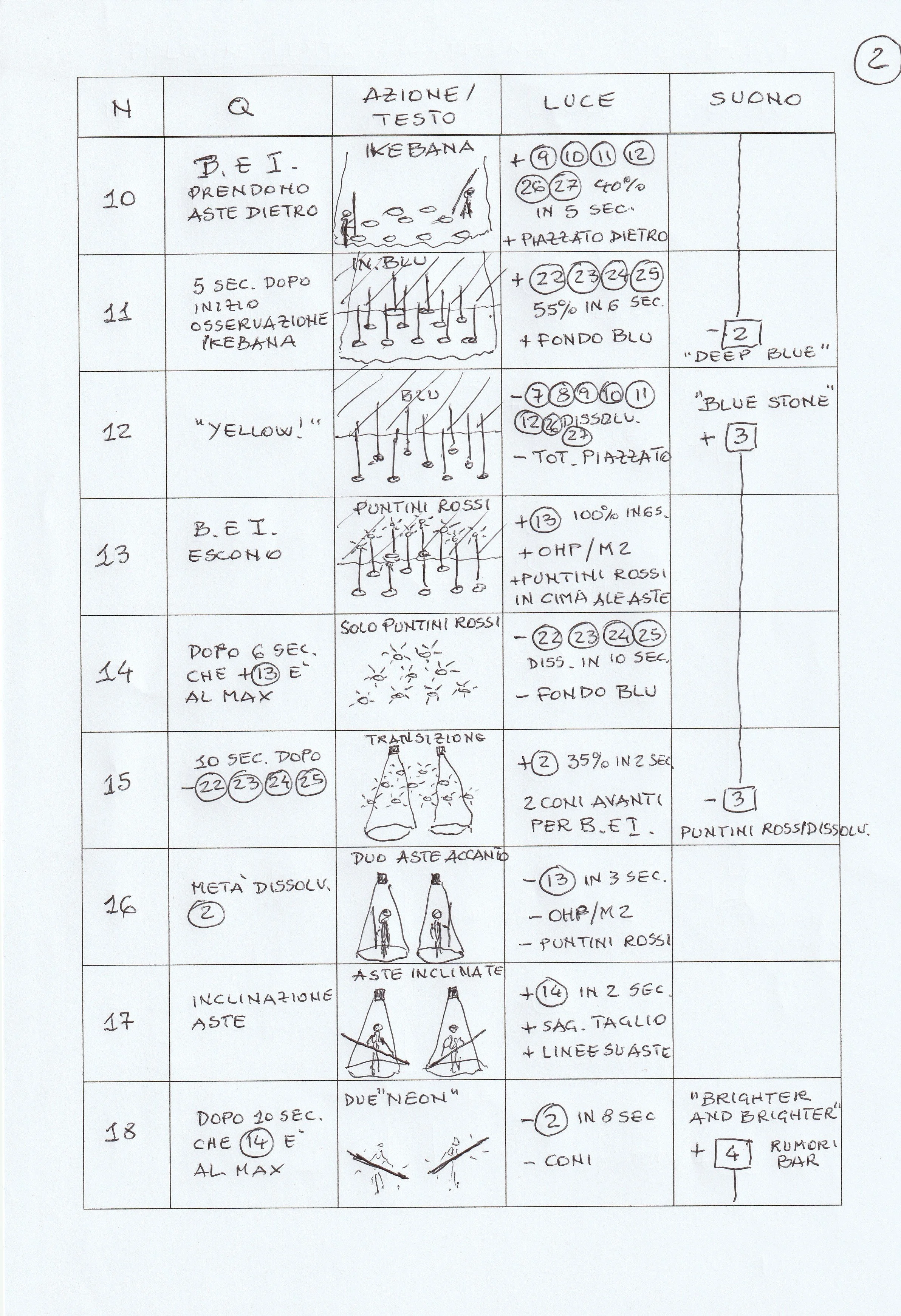

To provide a further element of understanding of what I mean by dramaturgy of light, I present below a light score I elaborated for one of my theatre works according to a method I customarily adopt, together with the corresponding lighting plan. Exactly like a musical score, the light score also has a memory function, and is therefore used as a guide by those operating the console during repeat performances. The performance to which it refers is Folgore lenta (Slow Flash), a work dedicated to Yves Klein, produced in Austria in 1997 [16].

The score consists of a table with five columns: the first (N) lists the scene numbers in succession; the second (Q), indicates the ‘cues’ (in the text, in the actions, in the sound, or in previous light movements) for the lighting changes; the third (ACTION/TEXT) details the performers’ actions and any texts corresponding to the individual light ‘scenes’. The indications relating to the latter are in the fourth column (LIGHT), and concern the active lighting fixtures, numbered as in the lighting plan, and the manner and timing of their action in relation to the ‘cues’. Intensity is also indicated, as a simple point of reference, since these values vary from theatre to theatre. The final column (SOUND) concerns the numbered sound tracks and specifies the ‘cues’ for the entrances and exits of the pieces.

Reading each horizontal strip makes it possible to see the relationships between light and the other elements of the work (text/action/sound) at every moment of the performance.

Folgore lenta (Slow Flash), a performance lasting approximately one hour, as mentioned and as can also be deduced from the instrumentation employed indicated in the plan, was created many years ago. It is, in my view, significant in showing how lights can become part of a system of relationships and recurrences (in relation both to other lights and to the overall performance), in which each of them assumes an articulated role, almost like that of a ‘character’; and also in showing how luminous discourse can be concatenated like a ‘text’, becoming true and proper ‘writing’.

The system of recurrences, anticipations, returns, and combinations also explains the fact that the number of fixtures used is relatively contained in relation to the complexity and significance of light within the project.

One may note the presence of a particular projection device, the overhead projector (indicated with OHP: Over Head Projector). In the performance it was employed “in negative,” through the use of hand-crafted glass gobos, positioned according to the intended sequences on the luminous surface of the projector to produce forms of light (the gobos are indicated in the score with the numbered letter M).

Score and light plan of Folgore lenta (Slow Flash) 1997

Notes

[1] See A. Appia, Notes de mise en scène für den Ring des Nibelungen (production notes for Wagner's Ring of the Nibelung), in Id., Oeuvres complètes, ed. M. L. Bablet-Hahn, Lausanne: L'Âge d'Homme, 1983–91, vol. I, pp. 109–254.

[2] See F. Crisafulli, Active Light. Issues of Light in Contemporary Theatre, Dublin: Artdigiland, 2013 (original Italian edition: 2007).

[3] On the workshops, which I led from 1989 to 2015 in the various Italian Academies of Fine Arts where I taught, see F. Crisafulli, 'Light First. A Central Force in Theatrical Creation', in J. Collins, T. Brejzek (eds.), On Light, Theatre and Performance Design, vol. 9, no. 3–4, London–New York: Routledge, 2023, pp. 191–220; S. Tarquini (ed.), La luce come pensiero. I laboratori di Fabrizio Crisafulli al Teatro Studio di Scandicci, 2004–2010, Riano (RM): Editoria & Spettacolo, 2010. Detailed information on the workshop performances is in N. Tomasevic (ed.), Place, Body, Light. The Theatre of Fabrizio Crisafulli, 1991–2022, Dublin: Artdigiland, 2023, pp. 319–349.

[4] See F. Crisafulli, Active Light…, op. cit.

[5] See Ibid.

[6] K. Graham, S. Palmer, K. Zezulka (eds.), Contemporary Performance Lighting, London: Bloomsbury–Methuen, London, 2023.

[7] Ibid. p. 1.

[8] S. Palmer, Light: Readings in Theatre Practice, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

[9] C. Baugh, Theatre, Performance and Technology, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

[10] Y. Abulafia, The Art of Light on Stage, London–New York: Routledge, 2016.

[11] N. Moran, The Right Light: Interviews with Contemporary Lighting Designers, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

[12] T. Humalisto, K. Karjunen, R. Kilpeläinen (eds.), 360 Degrees: Focus on Lighting Design, University of the Arts, Helsinki, 2019.

[13] J. Collins, T. Brejzek (eds.), On Light, op. cit.

[14] See ibid., p. 128.

[15] C. Grazioli, A. Palermo, V. Perruchon (eds.), Lumière Matière: Variations et perspectives, Université de Lille/Giorgio Cini Foundation, Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, Villeneuve d'Ascq, 2025.

[16] Folgore Lenta (Slow Flash). Concept: Fabrizio Crisafulli, Andreas Staudinger. Direction, set design, and lighting design: Fabrizio Crisafulli. With: Irene Coticchio, Barbara de Luzenberger. Production KE Theater/Il Pudore bene in vista. Première: Cairo, International Festival for Experimental Theater, El Hanager Theatre, 2 September 1997.

By Fabrizio Crisafulli read also The Conceptual Framework of Corpoluce